The enduring fascination with legendary swords

Alamy

AlamyFrom Game of Thrones to Beowulf, we have long been fascinated by ancient blades. Quinn Hargitai explores literature’s love-affair with these deadly weapons.

Arthur had Excalibur. Bilbo had Sting. Arya Stark has her Needle. In many ways these blades have become just as iconic as their owners, which begs the question: why - in a modern world in which such ancient arms have become virtually obsolete - do swords still have the power to inspire such awe?

Ever since its publication in 1949, Joseph Campbell’s Hero With A Thousand Faces has had scholars holding literature’s most recognisable heroes up to the light, searching for shared patterns and traits indicative of the ‘hero’s journey’. While most of the scrutiny has revolved around the heroes themselves, the legendary swords they wielded have managed to carve just as memorable a place in the hearts of readers.

Alamy

AlamyLooking at A Song of Ice and Fire, this generation’s favoured fantasy epic perhaps better known through its TV counterpart Game of Thrones, we see author George RR Martin has eagerly taken up the torch in literature’s blade-filled canon. From Ned Stark’s giant greatsword Ice to the prophesied flaming Lightbringer, Martin has provided fans with a veritable storm of swords to obsess over. Now with the eighth and final series fast approaching, there’s good reason to believe that some of the more notable blades will play a pivotal role in the battles to come.

More like this:

As astute Game of Thrones fans already know, while there are countless swords shown throughout the series, only a handful are deemed significant enough to be given a name. Blades of Valyrian Steel - like Jon Snow’s Longclaw, Brienne of Tarth’s Oathkeeper, and Samwell Tarly’s Heartsbane - have stood out in the series for their exquisite forging, eternally sharp edges and their function as status symbols. Though a seemingly superfluous detail, the showrunners have made a special point of noting all the times these blades have changed hands over the course of the series; some have been melted down and reforged, stolen, or given as tokens of loyalty. As Valyrian steel was found to be one of the few substances capable of killing White Walkers, keeping track of who has a blade made from it has taken on a new gravitas in the final season now that hordes of undead have finally breached the Wall and begun their unholy campaign against the people of Westeros.

Alamy

AlamyWhile it would seem prudent to simply forge more blades of Valyrian steel, the forging methods of these blades were regrettably lost following the Doom of Valyria, a mysterious apocalyptic event reminiscent of the drowning of Atlantis. Though Martin is oft lauded for his defiance of the genre’s typical tropes, the mystical secrets of Valyrian steel being lost to time harkens back to longstanding, archaic mythologies.

The proclivity for the ancient, the belief that relics of bygone ages are superior to those of the present day, has long been a recurring theme in epic literature. In the Lord of the Rings series, JRR Tolkien makes it clear that all the best blades – Narsil, Sting, and Glamdring – were forged by the Elves of the First Age, thousands of years prior to the story’s main events.

Alamy

AlamyBut the trend doesn’t start there. Going back to Beowulf, one of the earliest works of the English language, one can see the same convention at work. In the climactic battle against the monstrous mother of Grendel, Beowulf finds he is only able to cut through her otherwise impervious hide with the aid of an ancient sword he finds hanging on the wall. When the sword’s hilt is later appraised, we learn its engravings date it back to a time when a race of “giants” were destroyed by a raging flood.

So why such a fondness for all things ancient? Wouldn’t one expect sword-forging techniques to improve over time, thus making newer blades better? Why do so many of these epics portray ancient relics as vastly superior to their the modern-day counterparts? The answer may lie in Anglo-Saxon history.

Swords and status

After the downfall of Rome, the Anglo-Saxons found themselves living in a world brimming with remnants of the empire’s former glory. In Old English texts, early Anglo-Saxon writers often referred to these marvellous remains as euld enta geweorc, or ‘the old work of giants’.

The superiority of these older swords reflects a perception that older times were filled with a magic that has waned as civilisation has progressed; they are relics serving as a testament to a mythical world lost to time. The inhabitants of Westeros view the remnants of Valyria in much the same way the Anglo-Saxons looked upon the ruins of Rome.

Alamy

AlamyA sword’s ability to endure over time is not merely a mythical convention, however. Compared to cruder weapons like spears and axes, swords typically required a more skilled blacksmith to forge them, meaning that they were often built to last. In addition to being more expensive to produce, swords also required a greater deal of training to wield properly, meaning they were often reserved for higher military ranks or those of an elevated social class.

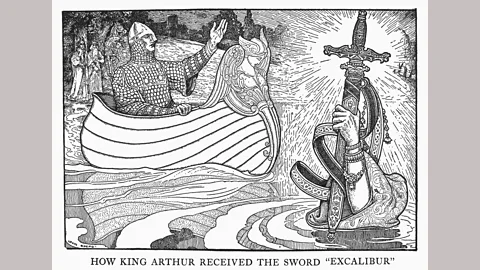

The result was that one’s sword and status were inextricably linked. And so it has also been in literature: King Arthur’s drawing of the sword from the stone marked him as the rightful king of Britain. Harry Potter and Neville Longbottom’s ability to produce the sword of Godric Gryffindor from the Sorting Hat identify them as ‘true Gryffindors’. These swords tend to have minds of their own, choosing only to present themselves to those deemed worthy enough to bear them.

Alamy

AlamyOn knife edge

Enter: Lightbringer, Game of Thrones’ most mysterious and elusive mythical blade. In the final series, Lightbringer is set to play a critical role because its appearance will identify Game of Thrones’ prophesied hero, the ‘Prince that was Promised’, just as the sword in the stone identified Arthur. Though it’s remained conspicuously absent over the course of five books and seven TV series, we’ve managed to learn a great deal about the blade through the Red Priestess Melisandre who describes it as a burning sword that will be drawn from the flame by Westeros’s true hero.

The notion that Lightbringer will be a sword of fire adds an even deeper layer of allusion. We’ve seen flaming swords appear in tales from sources as old as the Bible; after Adam and Eve are expelled from paradise, the gates of Eden are guarded by an angel brandishing a flaming sword. The sword of fire has reappeared in mythologies since, the most similar to Lightbringer perhaps being the blade Dyrnwyn from medieval Welsh traditions, which was fabled to ignite in a dazzling display only when clasped by its rightful owner. If Lightbringer is to follow this particular convention, perhaps we’ve already seen it on screen – but simply not yet in the hands of its rightful owner.

In each case, a blade of fire signifies more than mere status, but a power imbued by a divine force. To wield such a sword shows that the warrior is backed by some deity. Lightbringer is no exception, as we can assume its rightful owner will be the chosen one of R’hllor, the Lord of Light.

Alamy

AlamyWhether it is because of its ties to status, harkening to times long ed, or representation of the divine, the sword has managed to endure as one of humanity’s most treasured symbols. Even now that swords’ real-world use has diminished, we still flock to tales of brave heroes taking up a blade and slaying beasts in a far-off land. What’s more, the swords of modern stories like Game of Thrones still enchant us with the same mystical properties of those written about thousands of years ago. Just as Joseph Campbell argued that there is only one hero with many faces, perhaps there is just one sword with many hilts – a single blade destined to entrance us over and over again, century after century.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.